In recent years, fantasy settings based on various non-Western cultures have popped up more and more often as the genre has sought to expand beyond the pseudo-medieval European realms and folklore and mythologies most immediately familiar to readers in Western Europe and the US. With the growing popularity of works featuring previously ignored cultures and subject matter, or which seek new approaches to spinning classic adventures in a different light, Slavic settings and stories are beginning to occupy an unexpected place in modern fantasy literature.

There is a special flavour that sets these stories apart, reflecting a culture which inspires both Western writers and local Eastern European writers alike. While the high fantasy settings that characterize the writing of Tolkien and so many other classic works of classic fantasy remain captivating, so too are the Slavic vodyanoys and rusalkas, the vast expanse of the Russian Empire, and the myths and legends of the Balkans.

Foreign audiences often tend to exoticize various Slavic cultures, having relatively little access to our literatures and history. Partially, the narrowness of their perception comes from the basic tendency to divide the world into ‘us’ and ‘them.’ While this tendency can seem unavoidable, it obscures our perspective. Thus, Western scholars have long tended to juxtapose their ideas of a ‘developed and progressive West’ with their conception of a ‘backward and barbaric’ East. One of the first thinkers to address this issue and challenge the existing bias was Edward Said, who published his Orientalism in 1978. His work later became a must-read for baby-historians, inviting a string of follow-ups that examine the concept of ‘othering’ and how it is deeply rooted in all the spheres of our lives. But Slavic cultures are not exactly ‘Oriental’ in Said’s sense. Eastern Europeans face marginalization, but not colonialism, and are ‘othered’ for different reasons, mainly relating to their origins, religious backgrounds, and culture. Slavic cultures became the ‘other’ because of their unique geographical and political position between the imagined East and the imagined West.

It is not surprising that topics such as nationalism and marginalization dominate Eastern European history and literature, while Western discourses focus on colonialism and racism. This paradox has been addressed by historian Maria Todorova, who dedicated one of her most famous works to the idea of ‘semi-othering.’ Genre fiction, however, explores these pressing issues of marginalization and inability to adapt in its own unique way. It creates an approachable venue for readers to discover stories and settings that, despite their originality, are not as alien as they might at first assume. An exciting narrative can bridge the dichotomies between ‘us’ and ‘them’ and in doing so, create a community of fans instead.

Slavic cultures, historical figures, and places can all benefit when given an interesting, accurate literary introduction to a wide readership. This kind of spotlight has the power to change public attitudes and perceptions in the real world—for example, Ivan Vazov’s classical work of Bulgarian literature, Under the Yoke (written in 1888), was partially responsible for a shift in the British anti-Slavic sentiments linked to Russia’s foreign policies. Once Vazov’s novel became an international bestseller, it helped to turn attitudes of suspicion and distrust into curiosity and interest. Fantasy novels can challenge the same cultural ignorance while addressing a wide international audience. It is unfortunate, then, that so many works have difficulty reaching potential readers.

Translation Trouble

A factor that exacerbates the problem of Eastern European isolation is, perhaps paradoxically, the linguistic aspect: there are many languages, and neither the Slavic languages, nor Romanian (or Hungarian for that matter), are easy to learn—especially for an English speaker. Thus, a lot of classical fantasy and science fiction books from the region remain inaccessible to non-native speakers. But there are certainly exceptions that managed to capture international attention and achieve great popularity over the years. One such classical novel is Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita—one of the first Eastern European urban fantasies that combines the supernatural and the Soviet. It is a fascinating book that features witches flying over Moscow, a talking cat, a genius writer, the brilliant and tormented love of his life—all intertwined with the Biblical story of Pontius Pilate. It transcends genres and offers a truly unique view of the Soviet Russia. It is comparable to what Catherynne M. Valente attempts in her Deathless, but written by an insider who lived in the Soviet Union. And Bulgakov is not the only writer from Eastern and Central Europe who changed the face of fantasy and science fiction…

Central and Eastern European genre fiction scenes are rife with such luminaries as Stanislaw Lem, Karel Čapek, and the Strugatsky brothers, who are widely known and appreciated within the region and beyond. Moreover, the Čapek brothers (author and playwright Karel always credited his brother, the writer and painter Josef with coining the term), are perhaps best known around the world for inventing the word ‘robot’ (‘forced labourer’ in Czech). Apart from Lem and the Strugatskys, however, many other authors are cherished in the region but are not particularly famous in the West. Partly, this situation is the outcome of the decades spent by countries in the Soviet bloc translating each other’s bestsellers. Even nowadays, Russians actively translate contemporary Polish fantasy and embrace the work of authors like Jacek Dukaj or Jarosław Grzędowicz. Similarly, Poland has an array of brilliant translations from Russian. But it is a world of fantasy and science fiction that remains mostly inaccessible to foreign readers.

Nowadays, this situation is slowly changing. I am still, unfortunately, unable to share all the interesting fantasy novels that address Slavic cultures because most of them are not translated. Among them would be works by the Slovak Juraj Červenák, the Pole Jarosław Grzędowicz, the Czech Miloš Urban, the Russian Maria Semenova, the Serb Radoslav Petković… I’d like to think that the eventual translation of these works might further help to overcome linguistic obstacles and cultural isolationism, and create connections across genre fandom. For now, though, I’d like to offer a list of works already available in English that might serve as the vanguard for that larger shift.

My list of Slavic novels in translation will not highlight such well-known hits as Dmitry Glukhovsky’s Metro series, Andrzej Sapkowski’s Witcher series, and Sergei Lukyanenko’s Night Watch series. The works listed below are less familiar, but feature distinctly Slavic themes and offer interesting perspectives on our cultures, modern-day troubles, and complex historical legacies. Produced in a region where racial homogeneity is overwhelming, yet nationalism is rampant, most of these stories focus on issues such as social insecurity and instability, political isolation, and the desperation that comes from being used as pawns in the grand games of greater powers and empires. Even Russian fantasy, although coming from a state with prominent Imperial legacies, still conveys the same sense of nonbelonging and alienation. Changing political systems, upheaval, and lingering isolation leave their traces in our prose, one way or another.

Catering to adult and young adult audiences, the books I have chosen to highlight below share fantasy elements and uniquely Slavic sensibilities, ranging along the genre spectrum from magical realism to epic fantasy to speculative fiction. And I should note that while I’m focusing on Slavic literatures, I’m leave Romanian and Hungarian authors aside for now, although their literatures and legacies are closely linked to Slavic cultures, even if they do not focus on Slavic folklore—perhaps they deserve a list of their own. For now, I hope you enjoy the following recommendations:

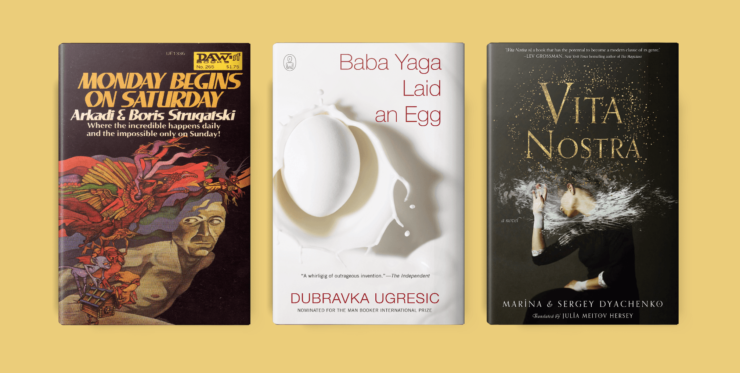

Monday Begins on Saturday, Boris and Arkady Strugatsky

Somewhere in Northern Russia you will find the “Scientific Research Institute of Sorcery and Wizardry,” where Soviet mages carry out their research and struggle with merciless bureaucracy. Sasha, a programmer from Leningrad, picks up two hitchhikers on his way home from Karelia. As he soon discovers, the two scientists are powerful mages, who offer him the opportunity to stay with them in a town called Solovets. It is there that characters from folk tales and Slavic myths reveal themselves, Soviet everyday life blends with magic, and a Grand Inquisitor works as a taxidermist. A Slavic version of Harry Potter for adults, this satirical novel hit the shelves in 1965. It was first translated into English in 1977, with a more recent version appearing in 2005.

The Inner Side of the Wind, or the Novel of Hero and Leander, Milorad Pavić

A unique blend of historical fantasy and magical realism from the most widely translated Serbian author. A scholar and a writer, Pavic tells parallel stories about two people living out their lives in Belgrade during the early eighteenth and twentieth century, respectively. Playing on the myth of Hero and Leander, the first part focuses on Hero, a student of chemistry, whose life is intertwined with that of a Balkan master builder. Separated by two centuries from Hero, Leander struggles to survive the strife between the Catholic Habsburgs and the Muslim Ottomans. The two storylines meet in the centre of the book, each one enriching the reader’s perception of the other. Unique in its form and masterful in its execution, this novel is a reflection on Balkan history with magical twists, murder, art, and nationalism woven throughout.

Black Blossom, Boban Knežević

A Balkan epic fantasy, featuring a classic bargain with a wizard, a fight for power, and history repeating itself. The nameless protagonist is a persecuted Serb whose journey, while magical, is strongly rooted in Slavic myth and Balkan cultural heritage. It is a unique epic fantasy that explores the horror and consequences of war crimes, first published in 1993. I would recommend it to everyone who might be intrigued by an unusual story involving a noble quest turned upside down and filled with wicked twists and historical metaphors. This book is, perhaps, one of the most profound fantasies ever written about war, with an underlying sense of being stuck between nationalism and an inability to find acceptance. Its depiction of the darker side of our mixed heritage is especially resonant for readers from Russia and the Balkans.

Baba Yaga Laid an Egg, Dubravka Ugrešić

Inspired by Slavic mythology and Russian literature, this is another beautiful blend of magic realism, urban fantasy, and mythology from a Croatian writer and scholar. This is also, perhaps, the most deeply Slavic of the books on this list. Baba Yaga is a triptych featuring a writer taking care of her elderly mother and an admirer chasing her across Slovenia, a dissertation about Slavic folklore, and a hotel resort in the Czech lands. It is a retelling of a myth of the titular crooked witch from Slavic folktales set in modern times and with modern themes, centered around a set of Slavic women and their magical and slightly absurd stories.

Vita Nostra, Marina and Sergey Dyachenko

If you want a more metaphysical version of Harry Potter with a darker plot and notes of speculative fiction, then this is the book for you… During the summer holidays, young Sasha meets a mysterious gentleman who asks her to perform unusual and seemingly senseless tasks, offering strange gold coins as payment. Using the collected gold to enter the so-called Institute of Special Technologies, Sasha is forced to question her pre-existing ideas about reality and to develop new ambitions. You will not encounter magic wands and tame owls, here. Instead, you’ll slowly discover the dark and beautiful mysteries of the Institute, its teachers, and students—nothing is what it seems, and the illusions offered by Vita Nostra make for a beautiful read.

Kosingas: The Order of the Dragon, Aleksandar Tešić

A Slavic epic fantasy with unexpected twists, this book combines the epic scale of the Song of Ice and Fire series with Balkan history and legends. On the eve of the Battle of Kosovo, monk Gavrilo, the leader of the Order of the Dragon, is searching for the knight who, according to prophecy, will lead the members of the order against the hordes of Hades. But Gavrilo’s champion, Prince Marko, is not what he’d been expecting… Historical figures as well as creatures from Slavic folklore accompany Marko and Gavrilo on their quest, where familiar storylines are turned topsy-turvy and the reader’s basic assumptions about the genre are questioned. It’s a beautiful mixture of historical and epic fantasy set in the alternate version of the 14th-century Balkans.

The Sacred Book of the Werewolf, Victor Pelevin

A supernatural love story featuring a prostitute were-fox, a werewolf intelligence agent, and modern-day Russia with all its absurdity and beauty—it is a witty tale with a unique setting. The novel is neither romantic nor straightforward, but is a satiric fable that combines folklore with the grim reality of Russian life. (Note: you can read Ursula K. Le Guin’s take on the story here). If you love Russian fairytales and are searching for a unique urban fantasy that will challenge all the familiar tropes, this book is for you.

The Night Club, Jiří Kulhánek

Another paranormal story that starts in Prague, this is a novel about vampires and grand adventures. A young man called Tobias has been part of a mysterious group called the Night Club since his childhood…until one day the society is destroyed and Tobias is left for dead. When he wakes up, he discovers that he is on a modern-day pirate ship somewhere in Southeast Asia. But he must head back to the Czech lands in order to solve the mysteries plaguing his city and carve out his own fate. Among the many novels written by Kulhánek, this is the only one translated into English thus far, and perhaps it is also one of the most interesting to an international audience, due to its excellent descriptions of the secret lives of residents of Prague.

Ice, Jacek Dukaj

I could not help adding Ice to this list, although the novel is only in the process of being translated now and will, hopefully, hit the shelves soon enough. Ice combines alternative history, fantasy, reflections about science and power, and, of course, issues of nationalism and marginalisation. In an alternate universe where Poland is still under Russian rule and World War I never took place, a mysterious matter called Ice is spreading from Siberia towards Warsaw, threatening to engulf the whole Empire. With aethereal beings dwelling within the Ice, time and history itself change, leaving the whole of Eastern Europe in peril and altering human nature and even the laws of logic. The main character is a Polish mathematician who must balance between science and political intrigue while searching for his lost father in Siberia. Along the way, you will be tempted to question your existence, and also meet Nikola Tesla, scandalous Grigori Rasputin, lofty magical industrialists, and an impressive array of fascinating figures from Polish and Russian history. This book is historical fantasy at its best. (And, yes, I may be biased because Ice is my favourite fantasy novel.)

If you’d like to share and discuss your own favorite Eastern European works in translation, please let us know in the comments!

Teo Bileta is a social historian who focuses on Central and Eastern Europe in her studies. She also plays strategic boardgames and analyzes genre fiction from a historian’s perspective. She is currently based in Budapest.

I’m so excited to see the Strugatsky brothers get a nod! Even if I never read the book described here, I highly recommend “Hard to be a God” by them, they have more books which you may find very interesting indeed. The sad reality is that Russian doesn’t translate into English as well as into my native Spanish, I compared my Spanish edition of Trudno Byt Bogom (Hard to be a God) with its Ukrainian original, the Russian version and an English version, and the humor is gone in the English one.

I’ve always loved Brust’s “The Sun, The Moon, and the Stars” …

‘Hard to be a God’ is, perhaps, the most read/known work by the Strugatsky brothers. I had no idea it is available in English, though. It was popular in Germany for quite some time, also very appreciated in Poland and the Balkans. It’s interesting to discover, it has a great Spanish translation.

I’d associate the Strugatsky brothers specifically with ‘Roadside Picnic’. I didn’t know they wrote fantasy as well!

I could be wrong, but I really only started to hear the term ‘Eastern Europe’ after the retraction of the Soviet Union – ie, the term didn’t have any oriental connotations for me at all, it was simply an easy way of classifying for countries that had formerly been part of the Soviet union – ‘Western Europe’ being comprised of what was the old EC. Which in turn makes me wonder if the term will be largely meaningless in another few years?

The main character of the novel “Black Blossom“ is unnamed in the book, but no reader who knows the folklore and history of the Balkans has the dilemma of who it is. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Marko The book deals with the duality between historical facts and legends created by the people.

>> Ice is being translated.

This seems like a weird choice for novel to translate, it’s so profoundly steeped in Polish history, nationalism and traumas of last century that i am wondering how could you translate this so that westerners could get the background. I hope it would be as well annotated as Russian translation.

I was rather hoping to see Starosc Axolotla or Perfekcyjna niedoskonałość translated as they are more universal and would be nice to compare them to works of Peter Watts.

>>On topic

Meekhan series of novels by Robert M Wegner are a pure delight and while not specifically slavic are a nice read and are a great example of creating separate, vivid POVs telling a captivating story within an interesting world without a political message (an increasing rarity in SF/F)

H.L Oldie had some of his books translated to french but not enough to english.

Abyss of Hungry Eyes cycle is an amazing series of independently readable but ultimately interconnected novels with nothing that comes even remotely close.

Aonghus Fallon, you have pointed out an interesting thing about the term ‘Eastern Europe’ becoming irrelevant. I wish you were right. A lot of ‘othering’ depends on economic successes and the overall standard of living in a given country. If, for example, Serbia or Russia somehow become extremely prosperous (great lucrative opportunities, artistic freedoms, job security, etc.) a lot of damaging stereotypes will die out naturally. And so will visa restrictions. One day that will happen. I hope so.

Boban Knežević, thank you very much for commenting. You have just given away the juiciest part of the book! The whole point, at least for myself, was the joy of recognition.

ConfinedBear, Ice has an excellent translator as far as I know. What I am curious to know, however, is how non-Polish and non-Russian readers will perceive it. And I am definitely checking out Robert Wegner. He sounds great!

Eastern Europeans face marginalization, but not colonialism

Ukrainians faced colonialism for centuries – namely, Russian colonialism. The postcolonial issues are among the most important in the (post-)modern Ukrainian literature, including so-called “chimerical prose” (= the Ukrainian version of magical realism). The most important “chimerical” novel of the past decade – I dare say, the most important post-Soviet Ukrainian novel – Voroshilovgrad by Serhiy Zhadan was published in USA in 2016.

I LOVE VITA NOSTRA!!! I hope we get the rest of the trilogy translated!!!

The “Labyrinths of Echo” by Ukrainian author Max Frei is a favourite of mine, the first 4 books are translated to English. I wish more would be translated!

>>> Eastern Europeans face marginalization, but not colonialism

Ukrainians faced colonialism for centuries – namely, Russian colonialism.

As, of course, did Poles from the 18th Century onward. (And other, mostly non-Slavic Eastern European peoples.)

Not to mention the fact that people in southeastern Europe — including Bulgarians, Serbs, and Bosnians, as well as various non-Slavic groups — were conquered and ruled by the Ottoman Empire from the 14th and 15th Centuries up until late in the 19th Century, while groups such as the Czechs, Slovaks, and Croats tended to fall under Austrian rule.

(Although I half suspect, based on the confusing reference to Said’s Orientialism, that the author is perhaps working from an unconscious assumption that it’s only “colonialism” or “imperialism” if it’s being done by the British or the French.)

Aonghus Fallon @@.-@:

I could be wrong, but I really only started to hear the term ‘Eastern Europe’ after the retraction of the Soviet Union …

A quick search of Google’s Ngram viewer shows that use of “Eastern Europe” began taking off in popularity after WW2 — in other words, it’s a Cold War term. (I certainly remember people using during the 1980s…)

That’s very interesting, Peter – I guess it was a sort of euphemism for countries that were part of the Soviet Bloc, but not Russia? In Ireland, the term ‘Eastern European’ is a common identifier (e.g. ‘He’s East European’)- which I think is a relatively new thing, maybe because it’s easy to guess somebody is Eastern European (based on their accent) but not what part of Eastern Europe they’re from.

Thanks for including my book on your list! Glad you liked it. Now the whole trilogy is available on Amazon in English.

PeterErwin, you are partially correct. The term was coined before WWII. (Larry Wolf’s Inventing Eastern Europe deals extensively with the subject) But the modern notion of Eastern Europe only gained popularity during the Cold War.

As to colonialism, I’ll try to summarize my point here.

1. We should distinguish between ‘colonialism’ and ‘Imperial rule’ or ‘oppression’ in general. When you refer to the Balkan lands being incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, you cannot call Bulgaria or Serbia colonies. Indeed, severe restrictions were imposed on the Christian population (aka the Rum-Millet) before the Tanzimat reforms (the situation was not perfect in the late 19th century either), yet, the governing system of the Ottomans was not colonial in its’ essence. The Balkan lands were integral parts of the Empire, individuals from those lands could, for example, become politicians and military leaders (and there are many such examples). Yes, nationalist activists were oppressed, arrested and mistreated, but that does not define the Ottoman Empire as colonial. From the point of view of the Balkan Intellectuals, it was an oppressive state, but it was not a state, where they did not have any access to the Imperial centers, schools or lucrative opportunities. (actually, the Ottomans tried to attract the Rum-Millet individuals and engage them in education reforms, etc.)

As to the Russian Empire in the mid-19th century, the situation is somewhat similar. Ukraine and Poland were not ‘peripheries exploited solely for resources with populations largely irrelevant to the Imperial politics’. Ukrainian nobles were integrated into the Russian elites (one cannot say the same about any African elites, for example, if we talk about truly colonial empires). There was no racial or national ban imposed on them. Similarly, Poles and Ukrainians could travel, study at Imperial universities, become artists, bureaucrats, live in St, Petersburg (unless they were serfs…but then it’s a class distinction, not a national one). They could not promote their national causes, which was the way the imperial government oppressed minorities. But, again, such were the policies of most European Empires – the Habsburg, the Russian and the Ottoman are the ones that I’ve studied closely and can talk about in detail.

2. Mykhailo’s is right when he stresses the oppressive politics of the Russian Empire (I guess, he means the late-19th century and the rise of Ukrainian Romanticism). But Ukraine’s position in the Empire was again, incomparable to that of the British or French African colonies. Ukraine was an important part of the Empire (with super-important cities, universities, intellectuals, etc.). The Empire did much more than extract profit from the territory. Moreover, Ukrainian elites were relevant in the Empire’s internal policies during the whole long 19th century. Just to illustrate my point: an Indian could not become a Minister in the British Empire, but both the Habsburgs and the Romanovs had non-Russian and non-German individuals on very high positions. And those were not ‘rare exceptions’. A Hungarian (before and after the Revolution of 1848-1849) or a Ukrainian could become a minister. Check, for example, the Ukrainian Grand Chancellor of the Empire Alexander Bezborodko or the epic Prince Adam Czartoryski, Alexander I’s Minister of Foreign Affairs (also, his wife’s lover). That does not mean that many Ukrainian or Polish intellectuals were not oppressed. They were. The Polish Rebellions are a testament to that harsh imperial rule (and so is the so-called Wielka Emigracja aka the Great Emigration). However, neither the Russian nor the Habsburg Empire were colonial in the sense we, historians, treat them. Their governing system was not colonial. The only attempt at colonialism was made by the Habsburgs in Bosnia. But that’s a different story….

Aleksandar Tešić, thanks for commenting! I had the fortune to read it in Serbian, but now I can share it with those, who cannot. :)

On Amazon there are a couple of novels by Henry Lion Oldie (which is a joint pen name of two Ukrainian authors, Dmitry Gromov and Oleg Ladyzhensky) – “Songs of Peter Sliadek” and “Shmagic”. I’m not sure about the quality of translation (I’ve read the novels in Russian, and their language is very rich and difficult, so it may be hard to translate it properly into English), but I wholeheartedly recommend both of those books. “Songs of Peter Sliadek” is made up of novellas and short stories, connected by the titular Peter Sliadek, a bard who travels the medieval Europe, listens to stories and inadvertently changes history. Some of the stories are very good, some are simply amazing (I’d single out “I Will Repay” as my favorite). “Shmagic” is the first book of their “Pure Fantasy” cycle (but it can be read as a standalone novel), and, as the name of the cycle can suggest, it is a kind of pastiche/parody of a typical fantasy world, that constantly subverts fantasy tropes, while looking at serious themes from some quite unexpected angles. H.L. Oldie need some recognition outside the Russian-speaking world, they are truly amazing authors.

Thanks for this article! You talk a lot about translation here, and indeed the work of translators makes this very list possible — could you please name the translators of the works you list here? They deserve recognition as much as the authors themselves!

One of my favorite articles I’ve seen in quite a while, I keep coming back to this